Welcome to Close Reads! Leah Schnelbach and guest authors will dig into the tiny, weird moments of pop culture—from books to theme songs to viral internet hits—that have burrowed into our minds, found rent-stabilized apartments, started community gardens, and refused to be forced out by corporate interests. This time out, Paul Morton muses on the mid-’90s cult hit Sliders.

Sliders, a science-fiction series about a group of misfit interdimensional travelers, premiered on Fox in 1995, and it was, for a short few months, the favorite show of middle school sci-fi fans who preferred its light touch to the network’s hit The X-Files. Jerry O’Connell plays Quinn Mallory, the prodigy hero, and John Rhys-Davies his gruff mentor Maximilian Arturo. There is also Quinn’s love interest Wade Welles (Sabrina Lloyd) and an aging soul singer Rembrandt Brown (Cleavant Derricks). Throughout the first (and only good) season of the show, the heroes visit alternate versions of San Francisco. In one, the colonists lost the Revolutionary War and America still lives under a monarchy. In another, the world is ruled by a matriarchy. The best episode is “Eggheads,” which aired in April that year. It describes a world in which smart is cool, where people, in the words of Arturo, “regard intellectual achievement with the same sort of adulation we confer on movie stars or sports heroes. Rather sensible, if you ask me.”

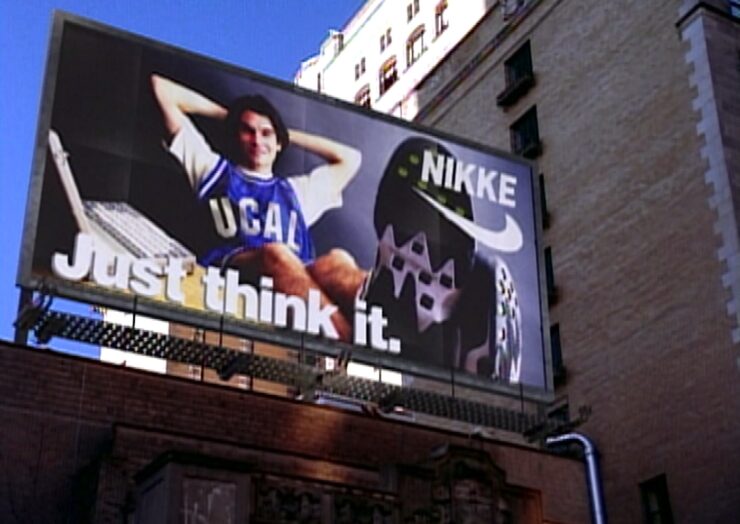

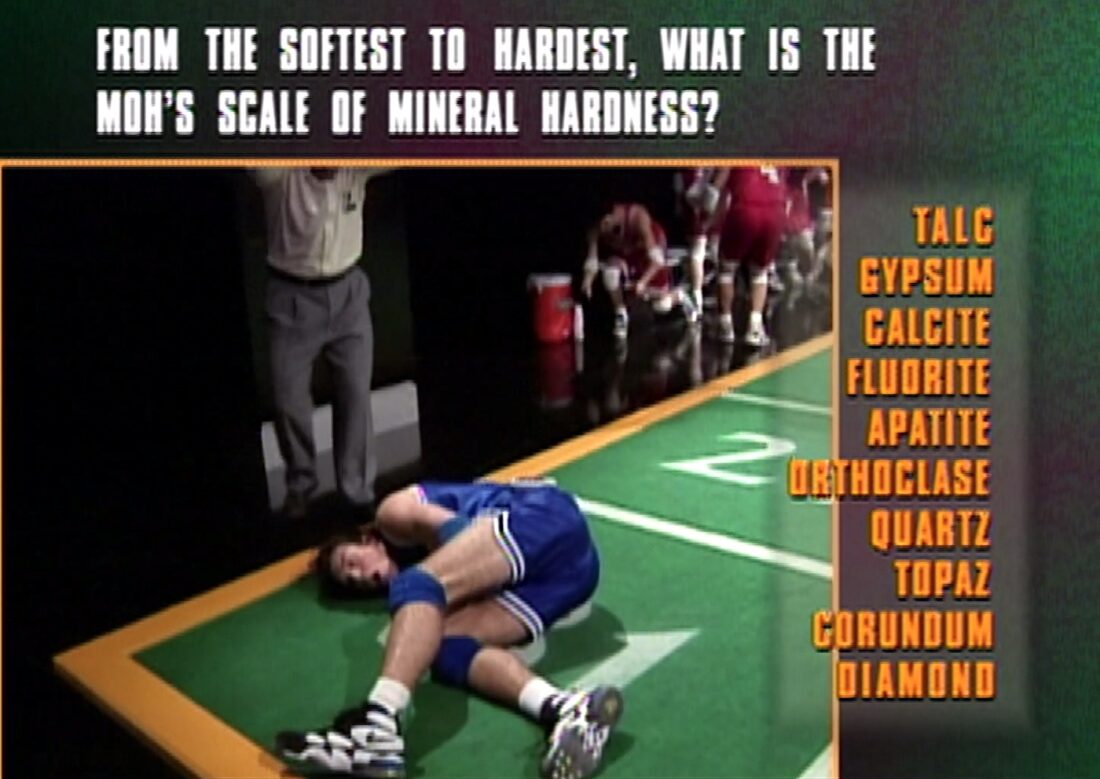

Every episode of Sliders is an exercise in heavy-handed world-building. In “Eggheads,” a pedestrian blasts Tchaikovsky from a boombox. Rap music videos describe trips to the library. “One warning, there will be no repeats: / Get out of my face when I’m reading my Keats.” Low-life criminals speak Latin and use terms like “cognitive dissonance.” In this world, Quinn is a superstar athlete of Mindgame, a combination of handball, chess, and science trivia. He appears in a “Nikke” ad with the tagline “Just Think It.” and on the cover of a box of “Weeties,” the “Breakfast of Geniuses.”

There is always a catch in Sliders and how or whether the characters would encounter their doubles is a key narrative question in every episode. In “Eggheads,” we learn that both Quinn and Arturo’s counterparts are in hiding. In a riff on scandals that shadowed Pete Rose and Michael Jordan, Quinn’s double has developed a gambling habit. He now owes money to the mob and is under investigation by the FBI for throwing games. Arturo’s double is a womanizer. He’s cleaned out the joint banking account he shares with his fed-up wife and run off to Europe. Both had announced to the world that they had invented their own sliding machine, but that claim turns out to be dubious.

“Incredible. We’re supposed to be in some super elevated intellectual society,” says Wade. “Everything is just as twisted as it is back home.”

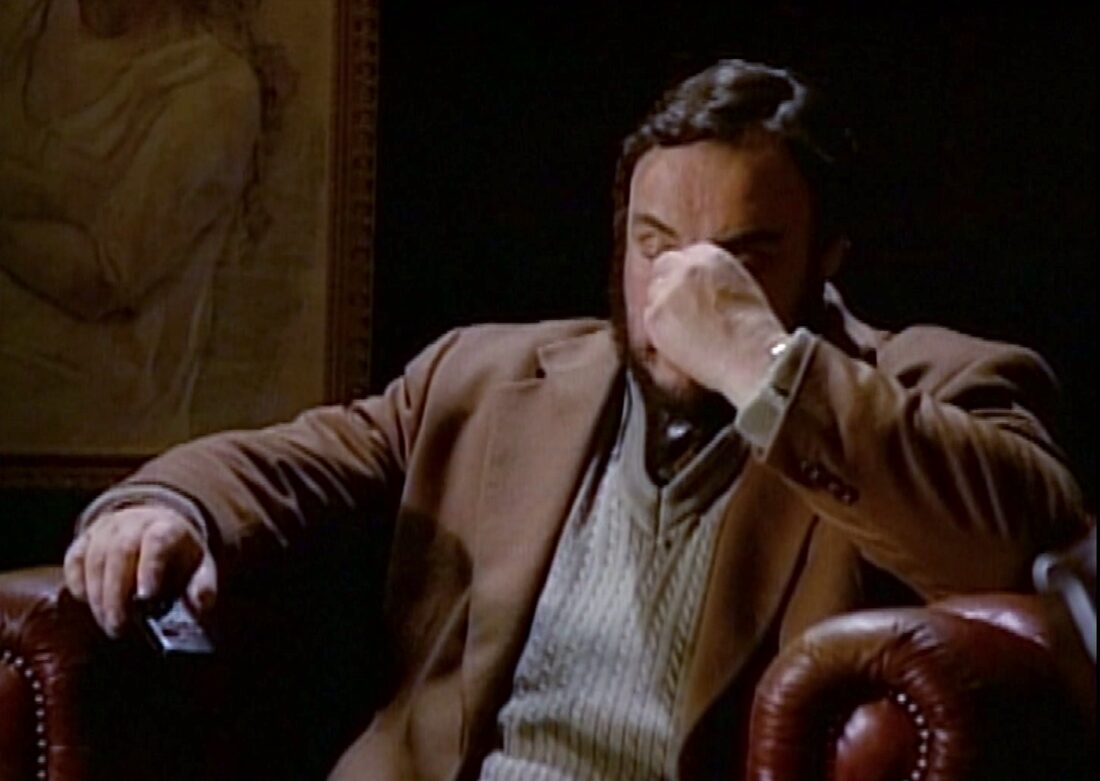

The tragedy runs a little deeper. In a genuine and heartbreaking scene, Arturo records a message for his double. In his own world, he lost his beloved wife to cancer at age 27, and it devastates him that another Arturo would squander a love so precious. Rhys-Davies has a booming, Old Testament voice, and it’s always wonderful when such actors reduce their register to quiet wisdom. “You inhabit a world which esteems the intellect. I inhabit a world that all too often appears to despise it. You have wealth, success, fame, and a wife that loves you. And yet, despite all of this, you are a fool.”

In the end, Quinn and his gang narrowly escape a chase from the agents of law and order and the mob. Before sliding to their next dimension, Quinn says the Latin equivalent of “So long, suckers!” A parting shot: Your world celebrates the mind, ours the body, but neither has anything approximating class or moral intelligence.

The episode made sense in the mid-1990s. TV still depicted smart people as socially inept. The nerd read comic books or classic literature. He—and it was always a he—knew how to use a computer and kicked ass in the science fair. “Famous writer” and “famous scientist” were both oxymorons in the sense that famous writers and famous scientists made only rare appearances on TV, which was where famous people lived.

Literacy was in decline and test scores were dropping. Talking heads complained that the national obsession with basketball got in the way of schoolwork and that rap music denigrated Black culture and language. I was an eighth grader in a magnet school, read obsessively, and took a fun Saturday class on Shakespeare. I knew nothing about basketball and mostly listened to my dad’s old Dylan LPs. Peace be upon you, Rabbi Rhys-Davies, for the show offered a good lesson.

I knew I had been born in the wrong time, because I knew that smart, or at least the show’s and my own version of smart, had been cool before. Classical music records sold well throughout the 1950s and ’60s and Charles Schulz explored his love for Beethoven in Peanuts. A quiz show turned the Columbia professor Charles Van Doren into a celebrity. The ballet dancer Rudolf Nureyev became a pop star and hung out with Mick Jagger. Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, William F. Buckley, Gore Vidal, Mary McCarthy, and James Baldwin debated politics and literature on talk shows. Walt Disney gave Wernher von Braun, the country’s leading rocket scientist, a platform to explain the wonders of space travel.

I don’t know if anyone who wrote “Eggheads” was inspired by that era. Van Doren was a sham. Mailer stabbed his wife and Buckley was a bigot. Von Braun had worked for the Nazis.

“Eggheads” wouldn’t make sense a few years after it came out, because smart would soon become cool again. The country’s most popular talk show host convinced her audience to read Russian literature. A satiric news show hosted prominent historians, Nobel economists, and one particularly charismatic astronomer. Rappers and stand-up comedians were expected to be great thinkers, and disappointed their fans when they betrayed their ignorance. An organization provided an online platform for public intellectuals to introduce their ideas on everything from the linguistics of texting to the biological causes of the obesity epidemic. The great entrepreneurs were renowned not for their ability to organize and take risks, but for their mystical understanding of tech.

And what did we get for it all? That talk show host platformed snake oil salesmen and charlatans. The brave public intellectuals of our day are peddling philosophical arguments in favor of misogyny and transphobia. The wealth of one late tech leader relied on the exploitation of China’s underclass. Others have created platforms that endanger democracy at home and abroad.

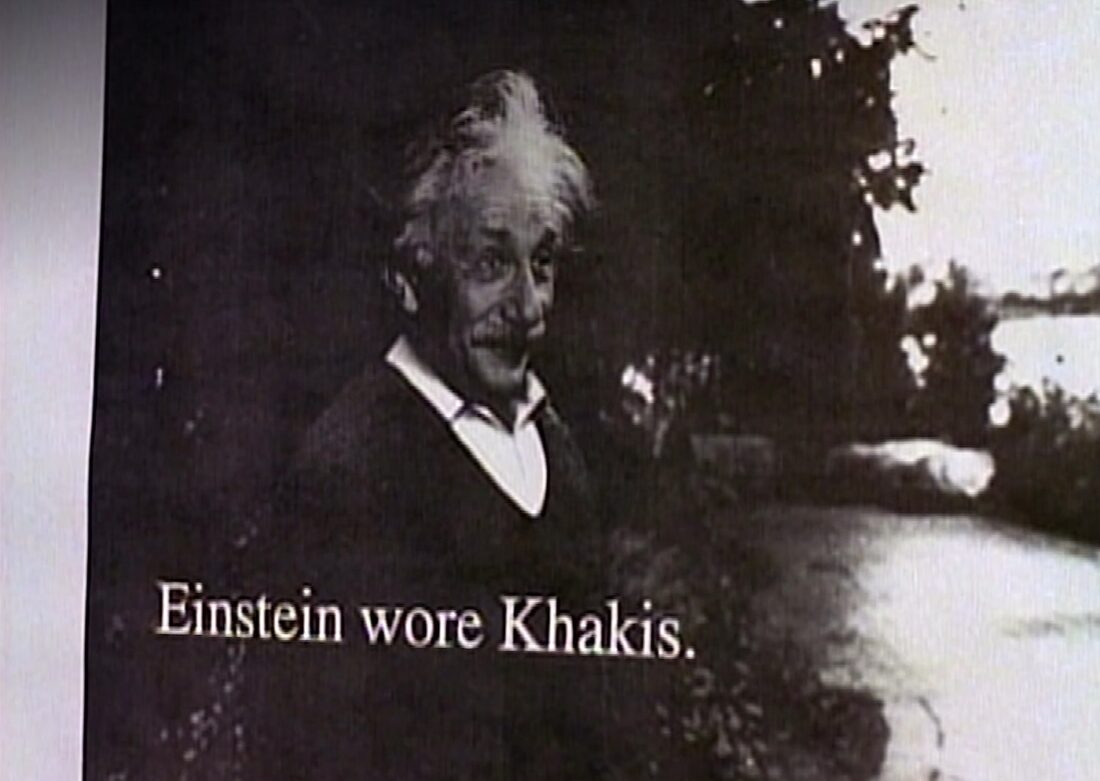

What Sliders gets right is that a world in which smart is cool, a world in which intellectuals are celebrities, is a world less interested in “doing smart” than it is in “being smart.” “Doing smart” requires patience and humility. Solid historical research involves hours in archives, analyzing dull documents about wheat production or, if lucky, fascinating letters from a war widow. Scientific research is about failing and failing and failing again and the great discoveries are as much a matter of luck as they are a product of genius. Writers can compose five or six full-length bad novels before they write one good one. The young boy asking for Quinn’s autograph in the opening scene of “Eggheads” doesn’t know any of that, nor does the average Gen Z-er meme-ing out an Albert Einstein or James Baldwin quote.

I suffered plenty of humiliations as a kid, but I never experienced any shame for my interests. The kids who were cut off from school lunch programs were oppressed, not lovers of literature. I was just sad. I wanted more people my own age who liked what I liked and wanted to talk about what I wanted to talk about, and I found some of that in my middle school. As an adult, I know plenty of smart-doers, but I guess they are still a minority of sorts. The smart-be-ers are running things and they have made us all miserable.